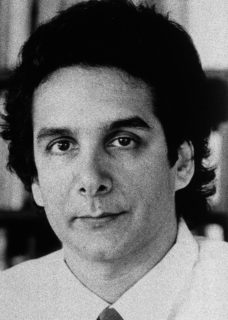

Neoconservative columnist Charles Krauthammer’s obituary in the Washington Post Friday carries a theme that gives us pause to consider the nature of humans today based on a singular word: curiosity.

Are we still curious?

The internal drive to know more, to question, to discover, to wonder why, to ask questions about why we believe what we believe, to adapt and change what we think, is the foundation of the species, let alone the most important attribute for a columnist.

Krauthammer died on Thursday, just days after announcing — in his column, of course, that his time was about up. He was 68.

By any measure, Dr. Krauthammer cut a singular profile in Washington’s journalistic and policymaking circles.

He graduated in 1975 from Harvard Medical School — on time, despite a diving accident that left him a quadriplegic — and practiced psychiatry before a restless curiosity led him to switch paths.

Instead of diagnosing patients, he would analyze the body politic.

Though much of the obituary reflects on his politics, it allows us the opportunity to examine why Krauthammer chose the paths he chose.

He told CSPAN once that because he grew up in the post-Holocaust years to parents who had escaped the Nazis, “It tempers your optimism and your idealism. And it gives you a vision of the world which I think is more restrained, conservative, if you like. You don’t expect that much out of human nature.”

In his younger years, he apparently wanted more certainty, choosing medicine over politics.

Amid the ferment of student revolution on college campuses, he grew disillusioned with politics and abruptly switched course to pursue medicine.

That discipline, he later wrote, “promised not only moral certainty, but intellectual certainty, a hardness to truth, something not to be found in the universe of politics.”

That was then and this is now, of course. Politics, is now the world of moral certainty requiring unquestioned adherence and the stifling of the curiosity that might threaten it.

After a swimming pool accident that left him paralyzed, he went on to become chief resident of Massachusetts General Hospital, then a speechwriter for Walter Mondale — a liberal — for a little while, then launched his commenting and columnist career, becoming a champion of neocons even while embracing some philosophies that made them seethe.

How else does that happen without the introspection that constantly requires us to examine why we believe what we believe?

It was “a restless curiosity,” the Post said.

“Maybe it isn’t a surprise that Krauthammer went from leftist Boston to a job as an assistant to the science adviser (Dr. Gerald Klerman, another MGH psychiatrist-mentor) in the Democratic Carter administration, and then, having caught the Washington bug of political tug-of-war, quickly drifted rightward to become the consistent conservative commentator of national renown,” Nassir Ghaemi, a psychiatrist, writes in Psychology Today.

In those long years in his prime, I found myself in deep disagreement with Krauthammer. It seemed to me that he had taken the “no good deed goes unpunished” motto too far, as if there was no use to good deeds at all. Maybe it was because he was Jewish and I was Muslim; or that he was from New York and I was from Tehran; or that he came of age in the radical 1960s and 70s, while I did in the conservative 1980s and 90s.

We were different; but we were both psychiatrists, with the same teachers. I could sense sometimes that he spoke from his psychiatric experience, from insights that came from long nights in the hospital; he seemed detached, cynical at times, but still one sensed experiences with human nature that his peers in political commentary never knew.

And then, in his last years, he stood up to Trump, at least in the president’s fellow-traveling attitude toward white nationalism. In that stand, Krauthammer showed that he preserved an integrity that power couldn’t impact.

“Some people are such a large presence while living that they still occupy space even when they are gone,” George Will writes today in his remembrance.

His death and our evaluation of his life’s journey is Krauthammer’s final “think piece,” forcing the rest of us to inquire of ourselves whether we’re properly tapping our human capacity for curiosity.

“I am sad to leave, but I leave with the knowledge that I lived the life that I intended,” Krauthammer wrote in his last column, an invitation for us to keep a question alive after his death.

Are we?